[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

The history of Mexico’s northern territory is, in the most literal sense, brief. Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821. By 1848, northern Mexico, which consisted of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, and Colorado was ceded to The United States.

Though it is not well-remembered, the new Mexican Republic (finalized in 1824) lacked citizenship in the north. Most Mexicans lived near Mexico City and could not be persuaded to move up to the northern provinces. Still, the Mexican government believed it needed a loyal presence if they hoped to secure the entirety of their new country. By the time they created their first federal constitution in 1824, Mexican officials had determined that they could entice Anglo-American settlers to give up their American citizenship, become Catholic, learn Spanish, and commit to becoming a part of the Mexican culture in exchange for ultra-cheap land in Texas. Empresarios like Stephen F. Austin began taking large land grants to recruit and settle hundreds of American families in Texas at the cost of about 12.5 cents per acre, a price that was only about 10% the cost of land being sold in America at the time. There were even greater price incentives for those who were willing to marry into the Mexican culture and have children.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

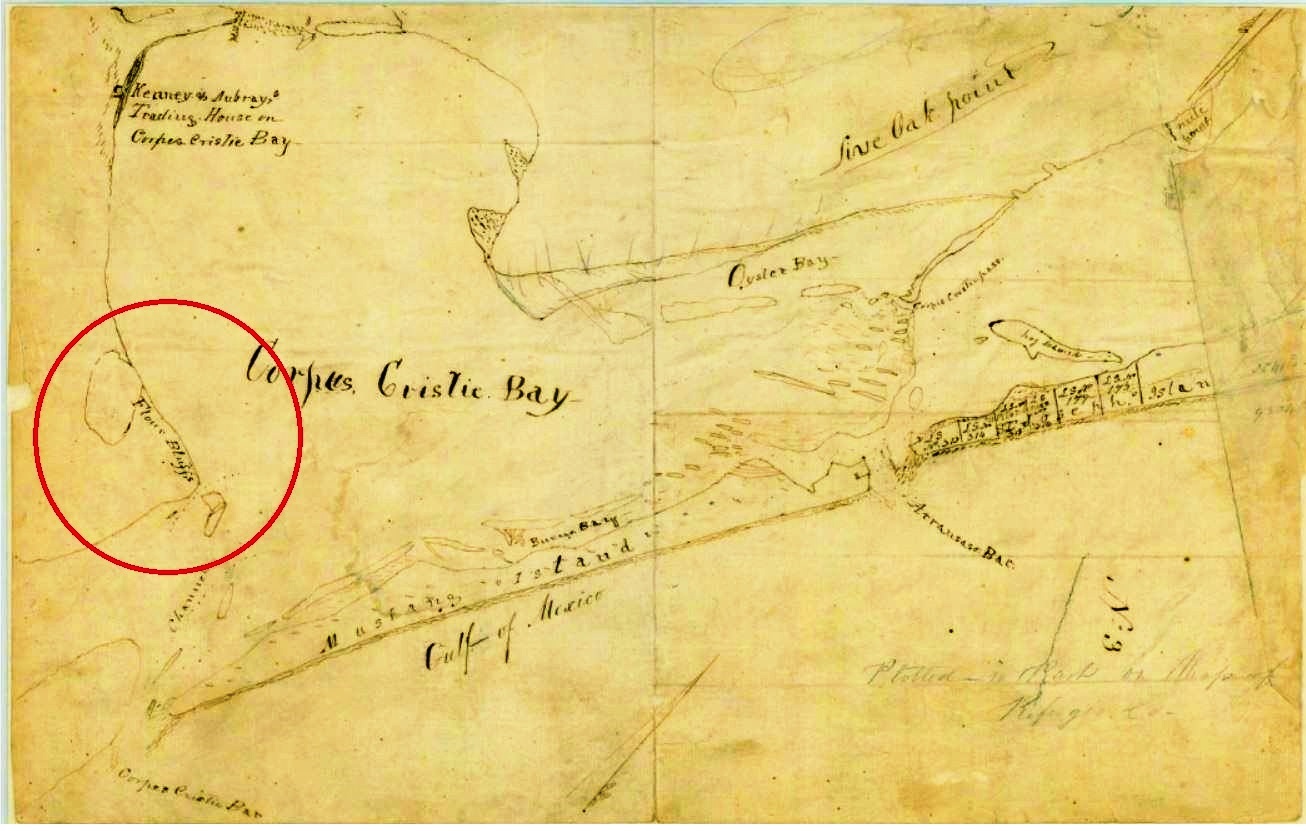

Between the years of 1821-1830, the Anglo-American presence in Texas exploded, eventually leaving Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent) outnumbered by Americans to the tune of about 10 to 1. In 1828, Mexico sent a government official – General Manuel Mier y Teran – to the Texas colonies to check in and see that their new American counterparts were living lives that were loyal to the Mexican Republic. To little surprise, he found that English was the dominant language, and a genuine loyalty to Mexico was lacking.

“As one covers the distance from San Antonio de Bejar to this town, he will note that Mexican influence decreases until arriving (in the colonies) where he will see that it is almost nothing… The ratio of Mexicans to foreigners is 1 to 10… It could not be otherwise than that from such a state of affairs should arise an antagonism (conflict) between the Mexicans and foreigners… Therefore, I am warning you to take timely measures. Texas could throw the whole nation into revolution…” – General Manuel Mier y Teran

In 1830, Mexico decided they had seen enough, and they attempted to close the border in Texas to prevent any further immigration of Americans. They attempted to enforce new laws and new taxes (under the Law of April 6th, 1830), but it was too late; the Anglo population who had once been referred to as Texicans had begun to simply call themselves Texans. The Texas Revolution broke out in 1835, and in less than a year, Mexico lost Texas in another mythically-charged story of the underdog.

In 1845, just 10 years after the Republic of Texas was born, America coined the term Manifest Destiny to implore the U.S. government to adopt Texas as a state in the union. Texas was accepted that winter as the 28th state. Convinced that America had devised a plan to steal Texas, Mexico furiously threatened war, and in the spring of 1846, The Mexican-American War began in a dispute over the southern border of Texas. Evidence suggests that American president, James Polk, consciously lured Mexico into the fight so that he could fulfill his presidential promise – Manifest Destiny. In 1848, after 2 years of fighting, the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo ceded Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and California to the United States. In the same year, gold was struck in Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California, which marked the beginning of the famously lucrative California Gold Rush – a race for wealth of which Mexico reaped no benefit.

In the Spanish culture, when land is gained, it is never to be ceded – not sold, and certainly not stolen. In 1832 – the same year in which Santa Anna became the president of Mexico, and several years before northern Mexico became Southern America – General Manuel Mier y Teran lay down on his sword in a fit of depression that stemmed from what he perceived to be the beginning of the end of his country. Perhaps Teran’s suicide expresses such a generalized sentiment. And though much more could be said about the loss of Mexico’s northern territory, one may suffice to say that, in the end, it was the unchecked, open borders in Texas that provided America with opportunity to proliferate, expand, and conquer nearly half of the Mexican Republic.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

In 2016, in the wake of an upset election in the U.S., perhaps Trump’s wall – be it virtual or literal, tall or small – is not the answer to the illegal immigration problems that face America today. But in flashing back on an important time in early Mexican history, it might be fair to conclude that Mexico wishes they had taken illegal immigration a bit more seriously than they did in the 1820’s.