[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

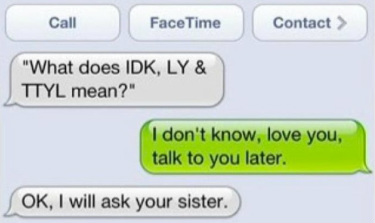

If the title of this article seems a bit ambiguous, it is. I did not write it; my 8th-grade granddaughter did. When I dropped her at school just as morning was breaking, I asked her to send me a text when she got inside the building so that I would know that she arrived safely. She agreed, then promptly forgot. When I finally received her text, I laughed out loud. Had she arrived safely, or was she distraught at not knowing the status of her existence? Texting, tweeting, and other modes of short, fast communication are ruining the fine art of writing. Add to that a general lack of practice in the modern English classroom, and we find that we have a generation of kids who are not adept at producing good writing. Let’s face it. They text and tweet more than they write formal compositions, which means they are practicing bad writing all day long. But wait, there’s more!

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

In the August edition of the Texas Lone Star, a publication of the Texas Association of School Boards, writer Ellie Hanlon addresses this topic in Texas. She refers to an article in the Education Post that describes the “angst of employers who have to manage far too many employees who cannot produce comprehensible written material.” She further notes that writing assessment results in Texas have been poor, with only 72 percent of seventh-grade students meeting even the very basic standards in 2015. As a teacher who taught writing successfully for nearly thirty years, I will add one more reason for the lack of writing skills in Texas: ten years of over 80% of Texas schools using a heavily criticized, error-riddled, “teach-to-the-test”, scripted, K-12 online educational curriculum (CSCOPE). Teachers are struggling to recover from its adverse effects in many areas, only one of which is writing. Because it was in existence for so long, even many graduating college students are unable to write a decent sentence or paragraph these days.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

Prior to CSCOPE, teachers who asked their students to write regularly, deducted points for style and mechanical errors, and insisted on complete sentences for all responses created good writers. Writing is one of those subjects that only has so much to learn in terms of the mechanics of the skill. Once students learn the rules, that’s it. No one is inventing new ones. However, as the saying goes, “If you don’t use it, you lose it.” In Frans Johansson’s contends that “deliberate practice is a predictor of success in fields that have super stable structures.” For example, in tennis, chess, classical music, and writing, the rules never change, so you can study up to get better and even become a master. One of the many weaknesses in CSCOPE was its lack of direct writing instruction coupled with lots of independent – not group – practice. When teachers and parents fail to insist that their children use the skills they have acquired – well and often – they will lose them. Students must practice good writing at least as much as they are practicing bad writing. So, how can the teacher and the parent help the child become a better writer?

Hanlon’s article offers up a few valid questions for all educators to ponder as they attempt to overcome the deficiencies in reading, writing, and speaking:

- Are students reading, writing, and discussing ideas every day in all classes?

- Are students reading and writing a variety of text types?

- Are students revising and editing written work by incorporating feedback from teachers and peers?

- Are students learning how to use reading, writing, and thinking skills to learn new material and develop ideas in ALL content areas?

Reading, writing, and speaking skills may be taught in the English class, but they must be practiced in all classes and – yes – even at home. Here’s a list of questions I devised for parents of these little destroyers of the language:

- Are parents discussing matters of importance with their children and asking them questions that promote thoughtful responses?

- Are parents asking their children to tell about their daily experiences using rich detail and good story order?

- Are parents taking the time to read articles from newspapers, magazines, and books with their children to prompt such discussions?

- Are parents insisting that their children speak clearly and explain or defend their thoughts?

- Are parents checking homework for legibility, clarity, and logical thinking and asking their children to re-write the responses when even one of these elements is missing?

- Are parents asking questions that encourage the children to be more specific in their responses? That is, are they teaching them to elaborate?

Even pre-school children can carry on intelligent conversations, think logically, articulate their positions on a wide variety of topics, and turn those thoughts into elaborate, coherent stories. Texas kids and teachers are recovering from the Dark Ages in Texas education, (aka, the CSCOPE era), a time when a one-size-fits-all curriculum traded creative thought and lively discourse in the classroom for mindless group work and repetitive lessons that were geared toward a test score instead of an education. If our children are to become adept at writing, we must ask them to read the master writers. When Arnold Samuelson interviewed Ernest Hemingway and picked his brain on how to become a master writer, Hemingway handed him a piece of paper and said, “Here’s a list of books any writer should have read as a part of his education… If you haven’t read these, you just aren’t educated. They represent different types of writing. Some may bore you, others might inspire you, and others are so beautifully written they’ll make you feel it’s hopeless for you to try to write.” When students read great writing regularly, their brains are exposed to the patterns of language in a meaningful way. The titles are below:

[spacer height=”20px”]

- The Blue Hotel (public library) by Stephen Crane

- The Open Boat (public library) by Stephen Crane

- Madame Bovary (free ebook | public library) by Gustave Flaubert

- Dubliners (public library) by James Joyce

- The Red and the Black (public library) by Stendhal

- Of Human Bondage (free ebook | public library) by W. Somerset Maugham

- Anna Karenina (free ebook | public library) by Leo Tolstoy

- War and Peace (free ebook | public library) by Leo Tolstoy

- Buddenbrooks (public library) by Thomas Mann

- Hail and Farewell (public library) by George Moore

- The Brothers Karamazov (public library) by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

- The Oxford Book of English Verse (public library)

- The Enormous Room (public library) by E.E. Cummings

- Wuthering Heights (free ebook | public library) by Emily Brontë

- Far Away and Long Ago (free ebook | public library) by W.H. Hudson

- The American (free ebook | public library) by Henry James

- Not on the handwritten list but offered in the conversation surrounding the exchange is what Hemingway considered “the best book an American ever wrote,” the one that “marks the beginning of American literature” — Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (public library)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Long before Hemingway’s advice to Samuelson, Benjamin Franklin knew the importance of emulating the masters. He was so embarrassed of his writing skills that he sat for hours copying the writings of the literary greats. He knew something then that many have forgotten or just ignore: Practice makes perfect. Even the latest brain research supports what ol’ Ben was doing; he was learning the patterns of writing by practicing what good writers do. If we want to get better at anything, we must put ourselves in situations where we can hone the skill by learning the simple patterns of language that lay the foundation for understanding and producing more complex patterns through regular practice. Leslie Hart wrote in a scholarly article about how the brain is a pattern-seeking device.

The brain is not logical or sequential in the ways it takes in and makes meaning of input from the world outside. Instead, it is constantly searching for patterns to understand in the surrounding environment. In their instruction, teachers should allow students to identify, understand, and apply patterns. We cannot predict what any one particular child will perceive as a pattern because so much depends upon prior knowledge, the existing neural networking of the brain used to process the input, and the context in which the learning takes place.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

To be clear, my granddaughter knew what was wrong with her text, and she chuckled about it, too, but we had “the talk” anyway. She is not offended when her granny points out or corrects her errors. After all, everyone makes a mistake now and then, even Granny. (She really enjoys catching me out, as do most of my friends and family.) Her cousin got a similar talk from me when he was doing his math homework last week. He tried to use a sentence fragment to answer a math question that required that he give the reason behind a wrong answer from a make-believe student. He wrote: “Because she multiplied by 2 instead of 3.” I made him erase and write a complete thought with proper punctuation: “Because the girl multiplied by 2 instead of 3, she got the wrong answer.” I learned this from my seventh-grade English teacher, Miss Waterman. Thanks goodness she set me on the proper path of using complete thoughts because my senior English teacher, Mrs. Lawson, required that we stand and address her in proper English, which meant using good grammar, good sentence structure, and clear speech. It was good training. (She would be proud that I don’t allow children, mine or anyone else’s, to mumble an answer. Clear speech is as important as legible handwriting if the message is to be conveyed.) We must serve as the examples for proper speech and writing, planting language patterns in the brains of our children if we want to help them get better at such an important skill, a skill that is in danger of destroying our ability to express our thoughts.

For more information on how the brain works, visit: http://nationalgeographic.org/education/brain-games/