[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

“Make a loose fist of your hand. Imagine that the fingers and palm are the major part of Corpus Christi. The space between them and the thumb corresponds roughly to Cayo del Oso. The thumb is Flour Bluff,”wrote Bill Duncan in a Corpus Christi Caller-Times article from 1963. He, like many others, agree that the geographical location of the Encinal Peninsula greatly affected the historical – and even current – events of the area. Though settlement of the area did not occur until the turn of the 19th century, this sandy “digit” attracted some human activity.

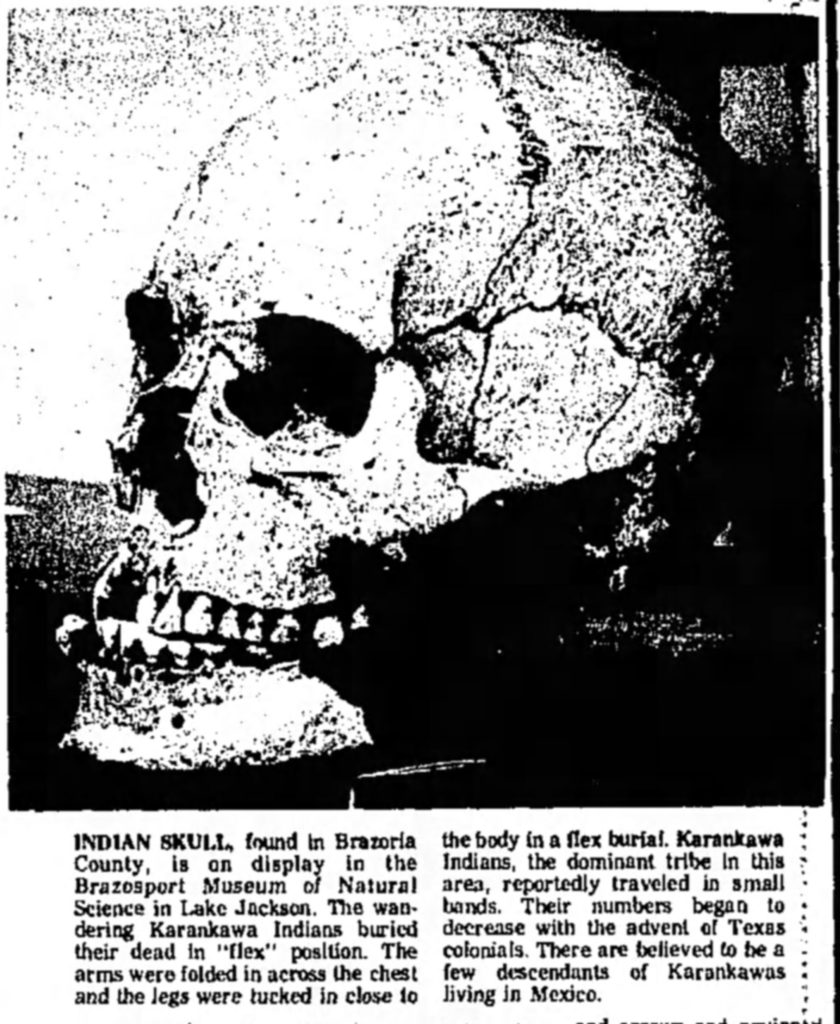

With the discovery of several burial sites of the Karankawa Indians (Carancquacas) on the shores of the Oso, one could logically conclude that these nomadic people would travel across the shallow Oso waters onto the great “thumb” seeking fish, shellfish, and turtles. These were staple foods for the pre-historic people called “dog-lovers” or “dog-raisers”, who, according to Carol Lipscomb, writer for the Texas Handbook Online, “kept dogs that were described as a fox-like or coyote-like breed.” The name Karankawa was a general designation of several bands of Indians who shared a common, though limited language, including the Capoques, Kohanis, and Kopanes. According to one source, the Karankawa word for “dog” translates to “kiss.” In addition to their limited vocabulary, they communicated with whistles, sighs, and guttural grunts.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

Many theories exist about how the Karankawa came to the Gulf Coast of Texas. This thoroughly coastal oriented tribe left an impression on all who encountered them. According to a May 24, 2016, Corpus Christi Caller-Times article by local historian Murphy Givens, “The men were over six feet tall and carried long bows of red cedar. Women wore deerskin skirts and smeared their bodies with alligator grease. The men’s hair was braided with rattlesnake rattles, which made a dry rustling sound when they walked.” Linscomb wrote that the bows “reached from the eye or chin level to the foot of the bearer” and that the men were tall and muscular and wore deerskin breechclouts or nothing at all. She goes on to relate how they painted and tattooed their bodies, and pierced the nipples of each breast and the lower lip with small pieces of cane. It seems that even the women tattooed their bodies and wore “skirts of Spanish moss or animal skin that reached to the knees.”

Most accounts of this extension of Paleo-American man claim that the Karankawa tended to travel in groups of 30 or 40 and broke into smaller “family” units to facilitate foraging. They could be hostile and warlike – even in their “play.” Givens relates in his article that Cabeza de Vaca was kept as their prisoner for years after he was shipwrecked on a barrier island in 1528. Twenty years later, all but two of a group of 300 survivors of a shipwrecked Spanish fleet were attacked and killed by a Karankawa band. Linscomb tells us, “Karankawas also participated in competitive games demonstrating weapons skills or physical prowess. Wrestling was so popular among Karankawas that neighboring tribes referred to them as the ‘Wrestlers.’ Warfare was a fact of life for the Karankawas, and evidence indicates that the tribe practiced a ceremonial cannibalism that involved eating the flesh of their traditional enemies. That custom, widespread among Texas tribes, involved consuming bits and pieces of the flesh of dead or dying enemies as the ultimate revenge or as a magical means of capturing the enemy’s courage.” Frequent encounters between the Karankawa and the European explorers, missionaries, and settlers led to many deaths from combat – and from epidemic diseases brought to the coastal areas by the invaders.

[spacer height=”20px”]

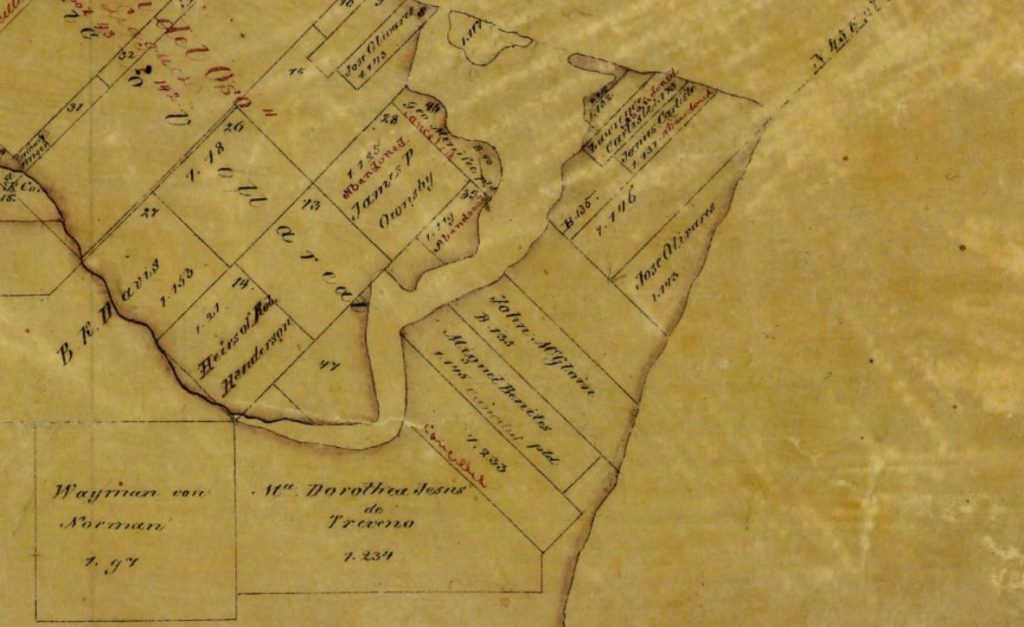

Map of 1853 Encinal Peninsula with names of the impresarios who were granted land on the Encinal Peninsula by the Mexican government

[spacer height=”20px”]

Though the Karankawa managed to survive 300 years of European contact, 1821 brought a different challenge for the indigenous group. Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, and the new government invited Anglo-Americans to the province of Texas. Over the next 15 years, the Karankawa would battle not only with the Anglo-Texans, but also with the hostile Tonkawas and Comanches. By 1836, the number of “dog-lovers” had diminished to the point that they were no longer considered a threat. It is believed that the few who remained moved into Tamaulipas, Mexico, where they suffered attacks from the Mexican authorities and were eventually pushed back into Texas, perhaps back to the shores of the Cayo del Oso (El Grullo), where they slowly disappeared into history.

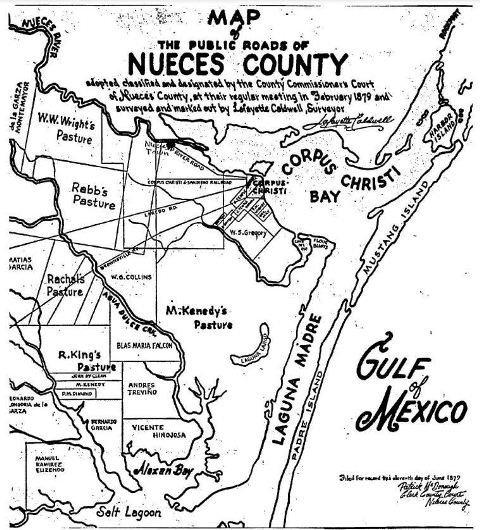

By 1850, Texas and Mexico were attempting to untangle the land ownership of the El Rincon del Grullo, “The Corner of the Grey.” According to Duncan, “It eventually went to Leonardo Longoria de la Garza of Tamaulipas by order of Texas Governor O. M. Roberts. Still there was no great rush to settle the area. One of the first surveys of the area, which appeared in the map, ‘The Public Roads of the Nueces County,’ and was adopted by the Commissioners Court in February, 1879, lists the entire tract from the Oso to Laguna Madre to Alazan Bay as ‘M. (Miflin) Kenedy’s Pasture.'” The land speculation of the 1800s by a Union colonel, Elihu H. Ropes and others, was responsible for the first breaking up of the large parcel and the arrival of the first settlers. Ropes filed a survey plat May 6, 1891, of the “Laguna Madre Farm and Garden Tracts”, which covered all of present Flour Bluff. It turns out that Ropes actually listed the 18-square mile plat (11,520 acres) as “Flower Bluff (sic) Farm and Garden Tracts”, some say to make the land seem more desirable. There seems to be some question as to whether Ropes ever actually owned land in Flour Bluff. Duncan writes, “More likely is it that the promoter made a deal with owners to survey the land and sell off portions under a ‘lot lease clause’ deal.” Sue Harwood, staff writer for the Caller-Times in 1959 wrote that Ropes did indeed buy the Flour Bluff land at $8 an acre. Regardless, this idea – like the ones that got him run out of town – fizzled.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

By 1890, the Texas Land Development Co. of San Antonio bought what was left of the peninsula after Kenedy bought much of the original grant from heirs of the Mexican grant. They started selling land between 1890 and 1900. Some of the first to buy this property have descendants living in Flour Bluff today. Mrs. Louisa Singer, G. H. Ritter, and E. Roscher were three who became some of the first settlers on the peninsula. At about the same time, Mrs. Henrietta M. King, who had acquired much of “Kenedy’s Pasture” in a partition of their lands, sold off by 1907, creating the southern boundary of Flour Bluff that joins the King Ranch. There, on the “thumb” between the Oso and the Laguna Madre, families started to take root in Flour Bluff, the little town that almost was.