To preserve the rich history of Flour Bluff, The Paper Trail News, will run historical pieces and personal accounts about the life and times of the people who have inhabited the Encinal Peninsula. Each of the stories comes from interviews held with people who remember what it was like to live and work in Flour Bluff in the old days. You won’t want to miss any of these amazing stories.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Top row (L to R): Daniel (Dad), Reynaldo (Rey, 4th child), Raul (Rudy, 3rd child), Rogelio (Roy, 5th child) Front row; Bottom row (L to R): Ricardo (Ricky, 7th child), Rafael (Rocky, 1st child), Hortensia (Mom), Rebecca (Becky, 2nd child), and Roberto (Bob, 6th child)

[spacer height=”20px”]

The people who first settled Flour Bluff have been called “mavericks.” A maverick think independently and does things his own way. Flour Bluff was an unincorporated area that lived by the unwritten codes of the people on the Encinal Peninsula. This attitude still exists even though the area was annexed against the will of its people in 1961. It was still a wild place known for ranchers and rodeos, fish fries and feuds among commercial fishermen, dirt roads and water wells and dirt roads leading to gas wells. It was a place where a hardworking family with a maverick spirit could carve out a life, and that’s what the Torres family did.

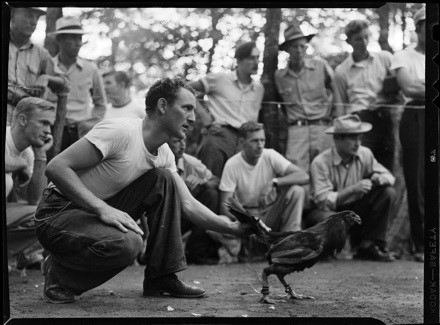

The Torres family arrived in Flour Bluff in 1954 at a time when the folks of Flour Bluff were thinking about becoming their own town. No one locked their doors, and dogs ran loose. Kids grew up playing, hunting, and fishing along the Laguna Madre and the Oso, and they sometimes took part in a little gambling for entertainment and profit. One such sport was cockfighting, an activity that has been traced back to the first century in Rome and has existed all over the world for centuries. Even the good people of Flour Bluff took part in the sport to make ends meet, even the Torres family. For them, it was a business opportunity.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

“On Sundays, we would get picked up by a bus to go to Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Church in town,” said Rey Torres. “After church, we’d go to Mr. Moore’s on Flour Bluff Drive for the rooster fights. We would take a bucket covered with a dish cloth full of tamales our mom made and sell them for 60 cents a dozen to all the rooster fighters. They were waiting on us every Sunday, and we always sold out. We had ten people to feed, so our mom was always looking for a way to make a little extra money.”

“Our dad brought in extra money fighting roosters,” added Rudy Torres. “We raised them, handled them, and fought them right here off Don Patricio. Our oldest brother, Rocky, was our handler.”

“The fights started at 1 o’clock,” said Roy Torres. “There was a mott of oak trees just behind the O’Brian house, the little cedar house that used to stand just in front of the pond. That’s where Mr. Moore held the fights. There weren’t many people living off Don Patricio and Flour Bluff Drive then. There was always a big group of men at the fights, and I would tag along with my dad.”

“That place of Mr. Moore’s got raided by the Texas Rangers,” said Rudy.

“That didn’t stop us though,” said Rey. “We couldn’t afford to lose those roosters. They helped bring money into the house. We fought at a pit on Upriver Road in town and in Alice sometimes, too.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

Cockfighting has been a popular sport for centuries and is still going on in all areas of the world. This 1950s photo shows a rural pit much like the ones in Flour Bluff at the same time. (Photo courtesy of WikiCommons)

[spacer height=”20px”]

“After the raid, the fighting arena was moved across Yorktown at the very end of Flour Bluff Drive,” said Roy. “About a half mile in, there was a gate that you had to go through to get to the pit. That arena was shut down because of something that happened between two guys who lived next to Eddie’s Bluff Saveway in a little motel. It was a guy named Red and his brother.”

“By the time the fights got started, these two guys were already drunk,” said Rey. “Everyone was around the pit watching the fight and betting with each other. Red and Mr. Aristeo Garcia, Lupe Garcia’s dad, got into a pretty heated discussion over something at the gate. That ol’ redheaded guy pulled out a .22 pistol and fired five times right into Mr. Garcia’s belly. The other men started dragging him to the gate, and his shirt came up so that we could see his undershirt with five bullet holes in it.”

“But it didn’t kill him,” said Rudy. “We were just teenagers when we saw that happen. That shooting resulted in that pit being shut down, but another one opened up soon after.”

“The third pit was on Caribbean about three-quarters of the way down on the right,” said Roy. “When they first started fighting at that spot, there was no parking charge. Then, they began charging a dollar a car. Everyone grumbled, but they paid the fee. One day I was there with my cousin, and I shouldn’t have been. I was driving a bright orange Toyota car. There was a Channel 6 newscaster back then who loved digging up dirt on people. rooster fights had started, and all of a sudden, we heard somebody hollering for us to look toward the brush. There was a guy crawling toward us with a camera! Then, we spotted a news helicopter flying over.”

“And you have to remember, a lot of those guys carried pistols,” said Rudy, “and anything could happen. Plus, the gate was small, which only let one car at a time enter or leave.”

Roy continued, “I looked at my cousin, and we knew what to do. We jumped in that car and took off. I don’t know which direction everybody else went, but I went left. Then, I lay low for about three days. On the news they showed the reporter crawling through the grass and the view from the helicopter of people scattering. They weren’t playing fair, and they certainly didn’t pay their dollar.”

“There was a fourth pit where the Don Patricio dump was across from what is now Sandy Way,” said Rey. “A man named Jose’ Moyar, who lived on Sandy Way, held fights at that dump. During the summers, he was a contractor for cotton pickers, so we all picked cotton for him. That was about 1959.”

“We worked with him at Chapman Ranch and way out Staples,” said Rudy.

“He picked us up in a big truck,” said Roy. “He had two 55-gallon wooden drums. We lived close to him, so he picked us up first. Then, he’d go around and pick up other workers. After that, he’d drive to the gas station near where Funtrackers is today. They had free water and free air. He’d fill the drums about three-fourths full and buy blocks of ice to drop in the barrels. Then, he covered the barrels with an old dirty canvas, and we used a ladle to get drinks while we worked. I was young, so my mom made me a special bag for picking cotton out of a flour sack.”

At a time when the Hispanic population of Flour Bluff was less than 10%, the men remembered how most of the people on the truck going to pick cotton were white, including a friend of theirs named Dwain Fuller. The also remember David and Dan Silva, Susan Galvan, and the Riojases riding in the big truck with them to the farms.

The brothers spoke of their trips to Arkansas to pick cotton and potatoes with their dad when they were all under the age of ten. There’s even a tale about Roy, who was really young, having a second mother on these trips.

“I was maybe four years old when we went to Arkansas,” said Roy, “just a suckling babe.There was a black lady there who had a baby about my age,” continued Roy after the laughter subsided. “She nursed me along with her baby. So, my dad told me that I had two mothers.”

(L to R) Rocky, Rey, Bob, Roy, and Rudy Torres long after their days at the rooster fights in the brush pits of Flour Bluff, flashing that winning family smile. (Photo courtesy of Rudy Torres)

[spacer height=”20px”][spacer height=”20px”]

The Torres brothers have hours of stories to tell of their experiences growing up in Flour Bluff. Much of what they hold dear is attached to Flour Bluff School. They are the kinds of people who befriend everyone and forgive those from the early days who treated them differently because of their last name or the color of their skin. They bring a different perspective to life in Flour Bluff, yet their stories of fun, adventure, school, and work often sound like every kid’s story who grew up on the Encinal Peninsula. As kids and young teens, their lives were centered around family because they did everything for and with their family.

Then, they began to grow up. Their oldest brother, Rocky, would leave Flour Bluff to serve his country as a Marine, blazing the trail for Rudy, Rey, Roy, and Bob, who would join after high school. Even their only sister, Rebecca (Becky) would marry a Marine. Only Ricky, the baby of the family would choose a different route to start life as an adult. Be sure to pick up the next edition of the Texas Shoreline News to learn more about those Torres boys.

______________________________________________________

Be sure to watch for the next story from The Paper Trail News to read stories from other longtime residents of Flour Bluff. Please share these stories. The editor welcomes all corrections or additions to the stories to assist in creating a clearer picture of the past. Please contact the writer at [email protected] to submit a story idea about the early days of Flour Bluff.