[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

Oh, how we love it when the Blue Angels roar into town like a band of barnstormers! In the days prior to the main event, these flying aces in their F/A 18 Hornets give us sneak previews on their practice runs, appearing out of nowhere, flying over the housetops, zipping across the sky, and leaving jet streams to alert all on the ground that the air show has come to town. This must have been how Flour Bluff’s Bernie Arnold and her cohorts affected the crowds in the early days of flight. Born September 2, 1899, in Bowie, Texas, to J.M. and Minnie Lee Harlan, Bernie roared into Flour Bluff in 1950. Her barnstorming attitude affected all that she did in life – including fighting annexation of Flour Bluff by the City of Corpus Christi – and gave her a place in local and aviation history.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Coming of age in the “Roaring Twenties” seemed to shape Bernie. Growing up in a town with the name of an Alamo hero who helped carve out the West, Bernie carved out a life in a male-dominated world. As a little girl, she watched as automobiles replaced horses and buggies. She saw how the airplane brought the possibility of leaving the earth. Bernie evolved just like the world – fast and furiously. She was a self-liberated woman who never let anything hold her down – not even gravity.

Bernie married Sam Coffman, a boy from her hometown, in 1918. By March 1919, she had her first son, Sam, Jr. Jim came along in 1920. Then, Bernie, like a handful of adventure seekers (mostly male) took up flying in 1921, just 18 years after the famous Kitty Hawk flight. It was her husband Sam who taught her to fly.

In February of 1921, Sam, Sr. and Bernie were flying with Jim, who was six months old at the time. Something went wrong, and Sam had to crash land their plane in the Trinity River bottoms outside of Ft. Worth, Texas. Jim survived the crash in his mother’s arms.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

Coffman, like many pilots in the early days of flight was a daredevil and earned money performing all kinds of aerial stunts. Coffman even tested a glider in 1930, which resulted in a broken leg, a broken ankle, and two broken wrists. Still he continued to fly because he loved it. “The only place there is to be with nobody bothering you except maybe God is at 10,000 feet and all alone,” said Sam Coffman, Sr. to a Caller-Times reporter in the 1970s. But, for Sam, just being a pilot wasn’t good enough.

[spacer height=”20px”]

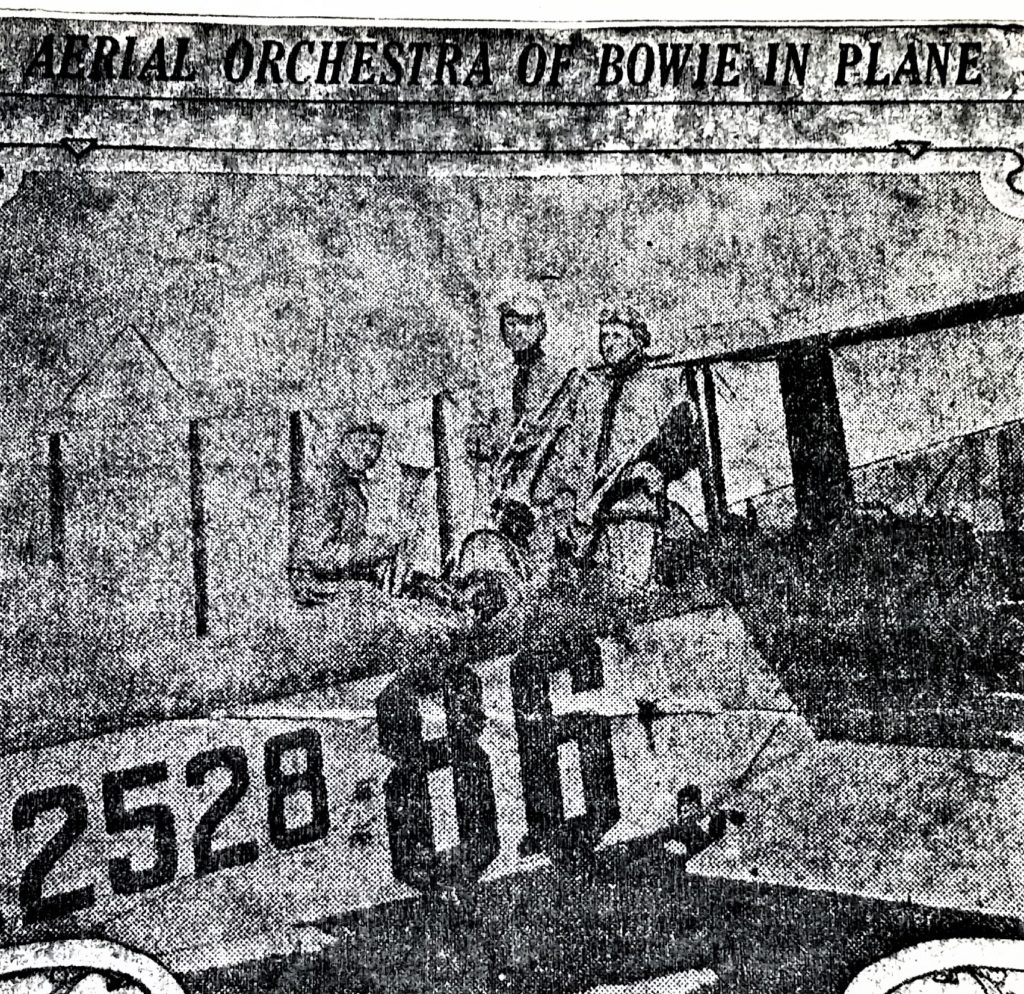

Sam Coffman, on the left, piloted this orchestra to an elevation of 5,000 feet while they played “When You and I Were Young, Maggie.” (Photo from Coffman family collection)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Sam was an aviator and inventor, an “aeronautical engineer” before the term even existed. He designed, built, and produced the Coffman Monoplane, a three-passenger cabin plane that sold for a few hundred dollars and was considered by other aviators to be ahead of its time. Coffman’s monoplane flew higher, faster, and better than most small planes of her day, according to an article in Air Facts magazine. Big Sam’s life was taking off. He ran the Ft. Worth Flying School but was often called away to Oklahoma, where he was manufacturing his airplane, or to other parts of the country, where he demonstrated and sold his invention.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Sam left Bernie and chief flight instructor, Ross Arnold, in charge of the flight school while he was gone. It was during this time that Arnold put Bernie back in the air. Bernie had been grounded in the years when she was starting her family, but she was ready to take to the skies again. After 20 hours of flight instruction from Arnold, Bernie did something that would make history. On October 13, 1927, she became the first woman to make a solo flight out of Meacham Field in Fort Worth, Texas.

“Flying isn’t anything like most people imagine it to be. I was afraid the first time but haven’t been since. That was six years ago in Bowie. Two days later I was ready to go up again. Haven’t had much flying since then until the last two months. When I wasn’t flying, I was watching the planes and studying the landing methods and take-offs and all the things about flying,” Bernie told a reporter after she landed her plane.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

During this time, Bernie found herself drawn to the man who put her back in the air, Ross Arnold. He was a barnstormer who took part in cross-country flights, and Bernie joined him in the life of a flying circus performer, going from town to town to show off her skills in loops and dives. This exciting job introduced her to the likes of Charles Lindbergh, Wiley Post, and Amelia Earhart. She even crossed paths with Howard Hughes when her husband Ross signed on as a pilot for Hughes’s film Hell’s Angels. Though she was billed as Miss Bernie Coffman, it wouldn’t be long before she ended her marriage to Coffman and married Arnold.

Mrs. Arnold spent the next few years flying around the country and into the lower Yucatan jungles. There she and Ross Arnold frequently flew across the Gulf of Mexico, hauling chicle’ from Yucatan to railroad terminals in Mexico. The gum business ended after three months of operation in 1927 when the natives became unexpectedly hostile to them. The duo then took their air show to the most remote points of the United States. Recalling her barnstorming adventures, Bernie said, “First we’d fly over a small town and buzz it soundly so that all the people would be attracted. Then with all the town’s eyes on us, we’d land in a pasture nearby for the crowd to flock around. In order to make enough money to buy gasoline, we’d take up passengers.” Arnold lost his life in July 1929 while on an endurance flight in Des Moines, sponsored by the Des Moines Register newspaper. Miraculously, a reporter riding with Arnold escaped serious injury. This event brought Bernie’s barnstorming days to an end.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Wing walking was just one trick that the early barnstormers used to draw the crowds and make a little extra money. (Photo from Bernie Arnold’s collection)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Arnold’s death took its toll on Bernie, but her interest in aviation lifted her out of her sadness. She saw new opportunities arise as commercial flight took off. Bernie signed on as one of the few ticket agents in the country and went on to manage an air travel bureau for four pioneering airlines out of Ft. Worth, Texas, just 68 miles from her hometown of Bowie. She worked for Braniff Air Lines, Cromwell Air Lines, American Air Lines, and Southwest Air Fast Express. Bernie was no longer a barnstorming beauty, but she found a way to stay involved in what was fast becoming a popular way of traveling for all.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Left to right: Sam H. Coffman, Bernie Coffman Arnold, Jim J. Coffman (Photo courtesy of Coffman family)

[spacer height=”20px”]

With the coming of WWII, Bernie took to the skies again. Her first husband, Sam Coffman, was doing his part for the war effort by training pilots for service. Both of their sons, who learned to fly in their teenage years, became military pilots. Lt. Sam Coffman was a flying instructor who died in a plane crash in Pecos, Texas, while on a training mission. Jim Coffman served as an Air Transport Command pilot out of Palm Springs, California. Bernie, with a desire to help the war effort coupled with her love for flying, volunteered for duty with the Air Transport Command, where she served until 1945. Bernie’s service to her country did not go unnoticed as she received an identification card on December 10, 1945, from Colonel R. J. Pugh that would grant her entry into any Air Force Station for the rest of her life.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

At the end of the war, Bernie hung up her wings and moved to Corpus Christi, Texas, at the invitation of her friend and fellow pilot, O. L. Holden. She and Holden went into business together, opening a sporting goods store on Water Street in Corpus Christi. They simply named it A & H Sporting Goods. “We were open 24 hours a day,” said Bernie. “We had to be. We didn’t have a door on the place.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

L. Holden, his daughter, and Bernie Arnold at A & H Sporting Goods on Water Street (Photo courtesy of Coffman family)

Soon, Bernie got wind of an effort to build a causeway across the Laguna Madre to Padre Island. Bernie’s spirit of adventure and keen eye for business prompted her to buy land at the corner of Laguna Shores Road and what is now South Padre Island Drive. The new causeway opened in 1950, and her new sporting goods store sat in the perfect place. Thousands of visitors to Padre Island stopped in at A & H Sporting Goods, owned and operated by Bernie and her son Jim Coffman and daughter-in-law, Inez Coffman. Bernie’s arrival in Flour Bluff, Texas, would lead her to new heights in business, local politics, and community service. Bernie would become a key player in Flour Bluff, the little town that almost was.